Hey kids, I decided not to post on the 18th to protest SOPA...lol, not really, I just was too tired to post again.

I wrote a 7-page "case studies" for school. Most of this you may know but here's the history of Sega for you. Hope nothing's factually incorrect. Just a nice read I suppose.

HISTORY & CORPORATE CULTURE OF SEGA

To this day, Sega stands out as one of the truly unique game publishers of our time. From producing some of the hallmark titles of our time to their lowest points, there is always something unique to the corporation. Unlike other “picture-perfect” companies like Nintendo and Microsoft, Sega paved the way with unprecedented hardware and quirky titles at the cost of miserable failures. With headquarters in San Francisco, Tokyo, and Brentford (UK), Sega’s culture throughout the decades still stands and is very much applicable in business today.

Sega was initially founded in 1940 as a small company in Honolulu, Hawaii. In 1951, it was moved to Tokyo and was given the name “Service Games.” The company distributed coin-operated devices such as jukeboxes and slot machines throughout Japan. Later it became involved in actual arcade development: Periscope, a 1966 submarine simulator, was the world’s first 25-cent arcade game. Eventually, in 1984, multibillion Japanese conglomerate CSK bought Sega and then the rest is history: a lavish history of arcade machines, home consoles, famous mascots, and a bad attitude.

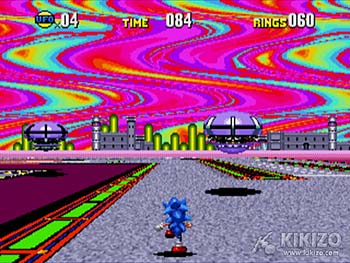

In the mid 80’s, Sega had already released two home consoles: the SG-1000 and the Master System. While both paled in comparison to the NES in terms of popularity, it was Sega’s arcade division that truly made a splash. Back then, Sega of Japan hired a gentleman by the name of Yu Suzuki. Often dubbed as Sega’s answer to Shigeru Miyamoto, he was multitalented in terms of production and programming. After his first game Champion Boxing (1983), Sega granted him the opportunity to create his own game. Based on his experience with fast cars and bikes, Suzuki formed his own subsidiary of Sega (AM2) to produce Hang-On (1984), a motorbike arcade game which utilized parallax scrolling and a tilting bike cabinet. This game was wildly successful which led to create OutRun, After Burner, and Space Harrier, three games which used the same graphics engine and style. The uplifting music and vibrant colors set the tone for Sega from the start.

Suzuki’s endeavors would continue into the 90’s. Using his expertise in hardware design and in collaboration with General Electric Aerospace (later known as Lockheed Marin), his AM2 team crafted the “Model 1” hardware board which was primarily used in Virtua Fighter (1993) and Virtua Racing (1992), the first apparent fighting and racing games of the time. Suzuki’s serious tone to games would later continue into in the future and paved the way for Sega’s arcade dominance and design philosophy for some time.

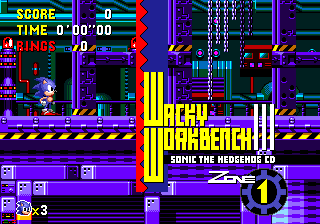

Sega of Japan’s stroke of good fortune didn’t end with Suzuki. In 1991, programming assistant Yuji Naka was given the opportunity to program Sonic the Hedgehog for the Sega Genesis. Sega’s tendency to reward programmers with their own games proved to be a huge hit as the Sonic character has become synonymous with Sega itself. The gracious Yuji Naka became the head of Sega’s Sonic Team subsidiary. Sonic the Hedgehog’s contrast to Super Mario of Nintendo fame would later reflect the two cultures of both clashing corporations.

Sega’s image was bolstered in the form of in-house competition. A great instance of this is the “war” between Toshihiro Nagoshi and Tetsuya Mizuguchi. Each recruited the assistance of Sega’s subsidiaries—Nagoshi to AM2, Mizugushi to AM3—to create their own arcade racing games. Nagoshi headed up Daytona USA (1994) while Mizugushi headed up Sega Rally (1995). At the time, Sega faced rival competition from other arcade developers such as Namco (Ridge Racer) and Midway (Cruis’n series). Neither game seemed to faze these two as they were interested in making games for the specific purpose of outdoing one another. With Suzuki as a mediator, it’s no surprise that both AM2 and AM3 arcade games from this period were some of the most critically acclaimed of all time thanks to this dichotomy.

Meanwhile, Sega of America’s campaign was in full swing, beginning with the Sega Genesis. While SoJ took a more serious approach to game design, SoA was much more laid-back and unorthodox. Developers of all types attended meetings vociferous and boorish, throwing out tons of ideas as mediators took notes. Anything was fair game for them. Needless to say, Sega became the “bad boy” of the gaming world as they tried to take out their rival, Nintendo.

Sega reached out with an edgy irreverence that captivated the 18+ year bracket. Campaign ads were launched with phrases like “Sega does what Nintendon’t” and the trademark “Sega Scream.” Even one infamous commercial boasted the Genesis’ “Blast Processing” power which was a completely made-up term for the sake of advertising. The Genesis was inundated with anticipated titles/sequels like Streets of Rage, ToeJam & Earl, and Sonic the Hedgehog which paled in comparison with Nintendo’s “clean” games like Mario or Zelda. To add to its edginess, Sega was more lenient on mature content as the Genesis version of Mortal Kombat featured more gore than the Super Nintendo version. Also, Sega recruited Michael Jackson to help design some of their games (Sonic 3, Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker). The “cool” image stuck with Sega as focus groups proved that teenagers who owned Super Nintendo consoles were generally afraid to admit it.

However, Sega’s eagerness to produce a greater quantity of content (over quality) proved to be their Achilles heel. This began with their console development on the Sega CD (1992), and the Sega 32X (1994). Originally intended to be their own stand-alone devices, hardware developers simply produced them as add-ons to the existing Genesis console. Savvy gamers are usually aware that the games for said devices were abysmal. The Sega CD was originally sold at $299 and consisted of a library of mostly movie-based games such as Night Trap. The Sega 32X costs only $159 at release but didn’t fare much better. Both consoles were difficult and not worthwhile to develop for. While Nintendo wasn’t immune from mistakes (Virtual Boy), Sega’s mindset was clearly to cover up any flaws with slick advertising. Nintendo’s steady lead over Sega continued.

Sega’s eccentric behavior carried over to other companies. Around this time, Sega was looking for companies to merge or buy out. They even set their sights as high as Electronic Arts or Disney (very unlikely). Eventually, in 1997, they nearly agreed to a merger with Bandai (Power Rangers, Digimon, etc.). Weeks before the merger, Bandai backed out of the agreement, citing cultural differences that could obfuscate their productivity. Later, Bandai would merge with Namco. It appears Sega never got along with anybody, even those they tried to become partners with.

The Sega Saturn (1994) was a huge improvement over the Sega CD and 32X as it rivaled the Sony Playstation in terms of capabilities. Fictional Judo master Segata Sanshiro served as the console’s mascot in Japanese commercials, training with a giant Saturn console, throwing people causing them to explode, and beating up people (including kids) who refused to play the console. These edgy commercials were not aired in the United States, which further proves Sega’s “in-your-face” mentality. Yu Suzuki and the AM2 team were called on to help craft the hardware which paved the way for a new series of successful Virtua Fighter games. Virtua Fighter 2, in particular, was sold at a ratio of 1:1 with the Saturn console itself.

Later, Yu Suzuki would attempt to create his magnum opus, Shenmue (1999), a luscious open-world game following the adventures of a young man trying to solve the death of his father. It was developed the Saturn before it was ported to the Dreamcast years later. The development cost of both Shenmue 1 and 2 was in the range of $70 million dollars. While the Shenmue series was critically acclaimed for having that Sega “mystique,” it was the beginning of the end of Sega’s glory days.

In 1998, Sega thoroughly planned the release of the Sega Dreamcast in coordination with Microsoft. Heralded as Sega’s “most glorious moment,” the console boasted arcade-equivalent graphics and colorful new IP’s, such as Jet Grind Radio, Space Channel 5, NiGHTS Into Dreams, Power Stone, Phantasy Star Online, Skies of Arcadia, House of the Dead, Super Monkey Ball, Crazy Taxi, ChuChu Rocket, Ferrari F355 Challenge (Suzuki owns his own Ferraris), Seaman, and even the titular Sonic Adventure (Sonic’s first fully 3D foray). It also featured SegaNet, an online browser/gaming service powered by a 56K modem.

However, things would quickly turn for the worse for the Dreamcast. The upcoming Playstation 2 console by Sony was graphically superior and also featured a DVD player. Bernie Stolar, President of Sega of America from 1997 to 1999, collaborated with Sega to develop the Dreamcast but noted that several hardware failures and a higher price ($199 vs $249) could cause the device to fail. He also barred RPGs and 2D games from the Dreamcast since he thought they were too “nerdy.” He also bullied Namco into releasing Tekken games for the Dreamcast alone. His predictions were correct but he was fired before the damage could be done. The Dreamcast was riddled with piracy and a poor development environment. Companies such as Electronic Arts backed out of working on the Dreamcast with the PS2 on the horizon.

The Dreamcast sold poorly in Japan and in Europe. Sega’s last-ditch effort was to provide American marketer Peter Moore with $500 million to advertise in the US. 2000 was dubbed the “Year of the Dreamcast.” Although the console became a cult classic, it wasn’t enough to bear the onslaught by the PS2. Sega permitted exclusive IPs to be published on other consoles. The Dreamcast ceased production in 2002. 10.6 million units were sold worldwide as of then.

To emphasize the Dreamcast’s failure, Sega lost from 1998 to 2002 a grand total of $1.5 billion (2002 inflation). To rub salt on the wound, Suzuki’s Shenmue series sold poorly and thus Sega “demoted” him in traditional Japanese business fashion. Sega managed to survive because of one of the greatest altruistic moves in gaming: CSK chairman Isao Okawa donated $695 million to Sega after his death in 2002. Though Sega lives, they’ve now been regulated to a mediocre third-party developer.

What led to Sega’s downfall over the previous decade? One of Sega’s ultimate strengths was in its hardware development. From Sega’s stellar arcade boards and cabinets from the 80’s-90’s to its striking home consoles, they were able to instill that unique culture through that medium. However, with the decline in arcades and the third-party transition, Sega lost a huge advantage over the competition. As a signal of change, Sega’s trademark indoor theme parks dubbed “Gameworks” began closing up across the world. The only explanation was that Sega, as a whole, was ambitious and willing to take risks and come up with completely unorthodox ideas, hence why the Dreamcast has such a stellar library despite the huge losses involved.

However, starting with their lackluster home consoles such as the Sega CD, Sega never really thought things through. This permeated through their corporate culture as they were forced to step back and re-evaluate the situation, only creating new hardware for arcade titles. Such quality, yet scarce titles such as OutRun 2 (2004), Ghost Squad (2004), After Burner Climax (2006), and Virtua Fighter 5 (2006) are attributed primarily to Suzuki’s AM2 team, widely considered to be the last true “gem” of Sega game development.

Things only became marginally better for Sega entering the 21st century. Sega was seeking mergers with various candidates, such as Nintendo, Microsoft, and Electronic Arts. In 2004, Sega agreed to a $1.45 billion deal in a merge with Sammy, a company heavily involved in manufacturing pachinko machines. Sammy’s CEO, Hajime Satomi, is rumored to be involved with the Yakuza and Sega-Sammy is used in his money laundering operations. Regardless of whether the rumors are true, Sega continued to wallow in the mire for years to come.

While Sega managed to earn meager profits throughout the mid 00’s thanks to their steady line of pachinko machines, very little good came out of it. Sega’s hallmark Sonic the Hedgehog series took a huge dive. Games like Shadow the Hedgehog, Sonic 2006, and Sonic and the Black Knight are considered abysmal even by typical video game standards, despite the fact the games managed to sell well. The situation became so bad that Sega of America President Mike Hayes had to assure the public that Sonic Team would hasten the production of new Sonic titles. To make matters worse, major Sega players such as Yu Suzuki, Yuji Naka, and Tetsuya Mizuguchi left the company to open their own studios.

While Sega may be developing few hallmark titles on their own, they’re seeing modest improvements entering the 2010 year. Mike Hayes has placed a specific emphasis on downloadable content and fresh new IP’s, stating that the profits from smaller, cheaper games can eclipse that of full-production titles. Classic arcade, Genesis, and Dreamcast games have been ported to modern online downloadable services such as Xbox Live and Steam, introducing old games to nostalgic gamers and new gamers alike. Sega has managed to publish some solid titles such as Bayonetta, Total War, The Conduit, Alpha Protocol, and Renegade Ops. They’ve also enlisted on the help from other studios such as Dimps and Sumo Digital to help create more quality Sega-related titles. Also, Sega still continues to produce some quality in-house titles, such as Yakuza and better quality Sonic the Hedgehog games.

Sega has adapted to the post-Dreamcast fallout with modest success. It is only natural that the market changes over time and Sega’s stubborn ways led to their downfall. However, they’ve held dear to their quirky nature since the very beginning. The fanbase still rallies around Sega, promoting new Sonic games on their own and creating fan content such as emulators of abandoned Sega arcade games. Even the eccentric Toshihiro Nagoshi, producer for Daytona USA, Super Monkey Ball, and Yakuza, proclaims that he will work for Sega for his entire career. All the meanwhile, Yu Suzuki and Yuji Naka continue to “supervise” at Sega.

Things can only get better for Sega from here. Once you’ve reached rock bottom, the only place to go from there is up.