I have this hough jazz book titled

Game Creation and Careers: Insider Secrets from Industry Experts by Marc Saltzman. I've had this book for many years already--I think it came out in 2003. My dad bought it for me. It contains much advice and insight from famous game devs like Will Wright, Hideo Kojima, Cliff Bleszinski, Peter Molyneaux, Shigeru Miyamoto and Gabe Newell. Subjects include characters, art, level design, programming, marketing, sound, et. al.

Now I've looked for Sega people and there are two--Yu Suzuki, Yuji Naka, Toshihiro Nagoshi, and Kenji Kanno (Hitmaker Studios which made Crazy Taxi).

Yu Suzuki has two sections and I might as well share them with you cause it's a bit interesting I guess. I could try to scan these sections but the book is way too fat for me to even attempt it:

------------

On Action/Arcade Game Design (pg. 21-23):

The honorable Yu Suzuki is a representative director at Sega-AM2 Co. Ltd. in Japan. He has worked on a number of worldwide products over the past few years, including Beach Spikers, the Virtua Fighter series (1 through 4), the Shenmue series, the Virtua Cop series, Hang On, Space Harrier, Afterburner, Virtua Racing, and many others. Whew!

His dream is for Sega-AM2 to be a top studio by the world's standards. "We would like to be a company that, when someone talks about 'a game company,' they immediately mention Sega-AM2," says Suzuki. He provides several pieces of good advice for a new game designer:

* Senior team members. As game development is in most cases a group effort, the most important matter is communication. In order to learn techniques effectively, it's important to find "good seniors." I recommend you go out and play other than in a place of work, and have a good friendship with them. By having a good relationship with them, you'll be able to obtain various kinds of information or advice. By combining obtained information/advice and your own ideas, you'll be able to work toward the goal without vain efforts.

* On-the-job training. Some companies provide educational programs for a certain period after entering the company. These are general or special programs, but the most effective one is "on-the-job training."

If they want to practice processing words, planners should not only type words, but try writing the imaginary planning document of a game. Programmers should try programming according to the plan their company may carry out (fly something, move cars, etc.). For example, if you have information that you'll be developing a game featuring a Porsche, instead of giving a test for other cars, start with Porsche cars from the beginning.

The same can be said for designers. For example, if you have information that you'll develop a fantasy game, you can create vfairies or creatures that suit fantasy, instead of flowers or glasses that have nothing to do with the game. I think that it's very important to always train yourself with images that you're likely to use in actual work.

* Self-investment. After you enter a company, you'll be salaried. Use your salary as much as possible for "self-investment" in order to add value to yourself. By raising your value in the company, their evaluation of you will rise.

* Pursue your hobbies as much as possible. For example, if you like watching movies, watch a lot of movies. Have at least one thing you're more familiar with than anyone else. Seen from other people's eyes, you might seem to waste your money. However, it will be your own experiences and a great help to create good games in the future.

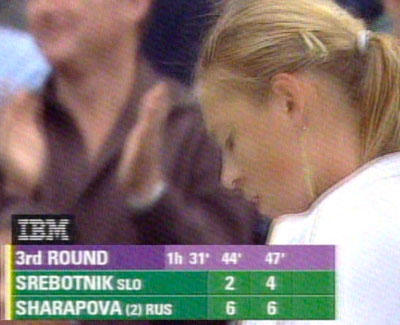

[displays image of Virtua Fighter & Yu Suzuki]

Yu Suzuki has helped create numerous Sega games for the home and arcade, including the Virtua Fighter series. Virtua Fighter 4 is shown here.

Suzuki says the most appealing part of the Virtua Fighter series is its multiplayer gameplay. He explains that it's not just simple "person versus CPU" gameplay: "For players, their opponent is a person through the medium of CPU. If a player changes, the gameplay itself will change, so it has a potential of limitless variation without running to pattern."

Asked to provide some do's and don'ts in game design, Suzuki says that it boils down to experiences success or failure in a game:

Players often have the opportunity to feel success or failure playing games. for instance, if it's a car-driving game, if you fail to turn curves for speeding too much, you'll feel you've failed. And if you succeed in turning curves, you'll feel you've achieved.

"Don'ts" include situations in which you can't explain how a player has failed, and he or she can't realize the reason in a clear way. For example, if a player suddenly gets shot from outside the screen and the game is over, no one will play that game again.

Where does Suzuki look for inspiration?

When watching movies, playing sports that have nothing to do with games, waking up in the morning, dreams, etc. I can't really specify occasions where inspiration comes. Generally, when I keep on thinking all the time, inspiration comes to me.

It's important to bring your mind, in which you'll meet inspiration. Even if you don't have an answer, by continually thinking, it will enter into your deep mind and by some chance you'll meet inspiration. Continual thinking [improves] the probability for inspiration to come. Conversely, if you think nothing, no inspiration comes.

What separates a great game from a good game?

* Passion.

* Never give up.

* Create a game carefully, thinking about the people who will play it.

In Chapter 6, Suzuki expounds on what makes for a great lead character in a game.

On Characters, Storyboarding, and Design (pg. 190):

Also at Sega is the one and only Yu Suzuki, who is responsible for such fantastic games as the character-driven Shenmue series, the Virtua Fighter series, the Virtua Cop series, Hang On, Space Harrier, and others.

Although Chapter 2 houses Suzuki's answers on creating fun and challenging video games, here we just asked him one question: How does he create such great characters as Ryo in Shenmue? Suzuki says:

What's most important is originality. Also, by tightly creating invisible parts like background stories or personalities of the characters, later development opportunity will be broadened. And lastly, a note on self-promotion: It's necessary to make an active effort to gain more recognition, like exposure or advertisement to media such as magazines or home pages.

------------

Hmm, well this book is damn outdated nowadays, but I still think it's relevant. I like how he encouraged you to pursue your hobbies and increase your self-value. That combined with inspiration can make you a valuable weapon in the game industry. Too bad the articles don't mention OutRun, but you have to realize that OR2 came out in 2004, a year after the book was published.

I also liked how he mentioned car driving in the do's and don'ts section. Apparently, his games aren't like Cruis'n games where you get a little love tap from the AI car next to you and you wreck and can't win for NO DAMN REASON at all. Stupid rubber band AI crap. At least with Sega racers, if you win, you know you did some things right. If you lose, you know you screwed up. None of this roll of the dice crap.

And that's all from Suzuki-San. I'm going to Nagoshi, Naka, and Kanno later, but damn, it took a long time to just type up this so we'll see later.